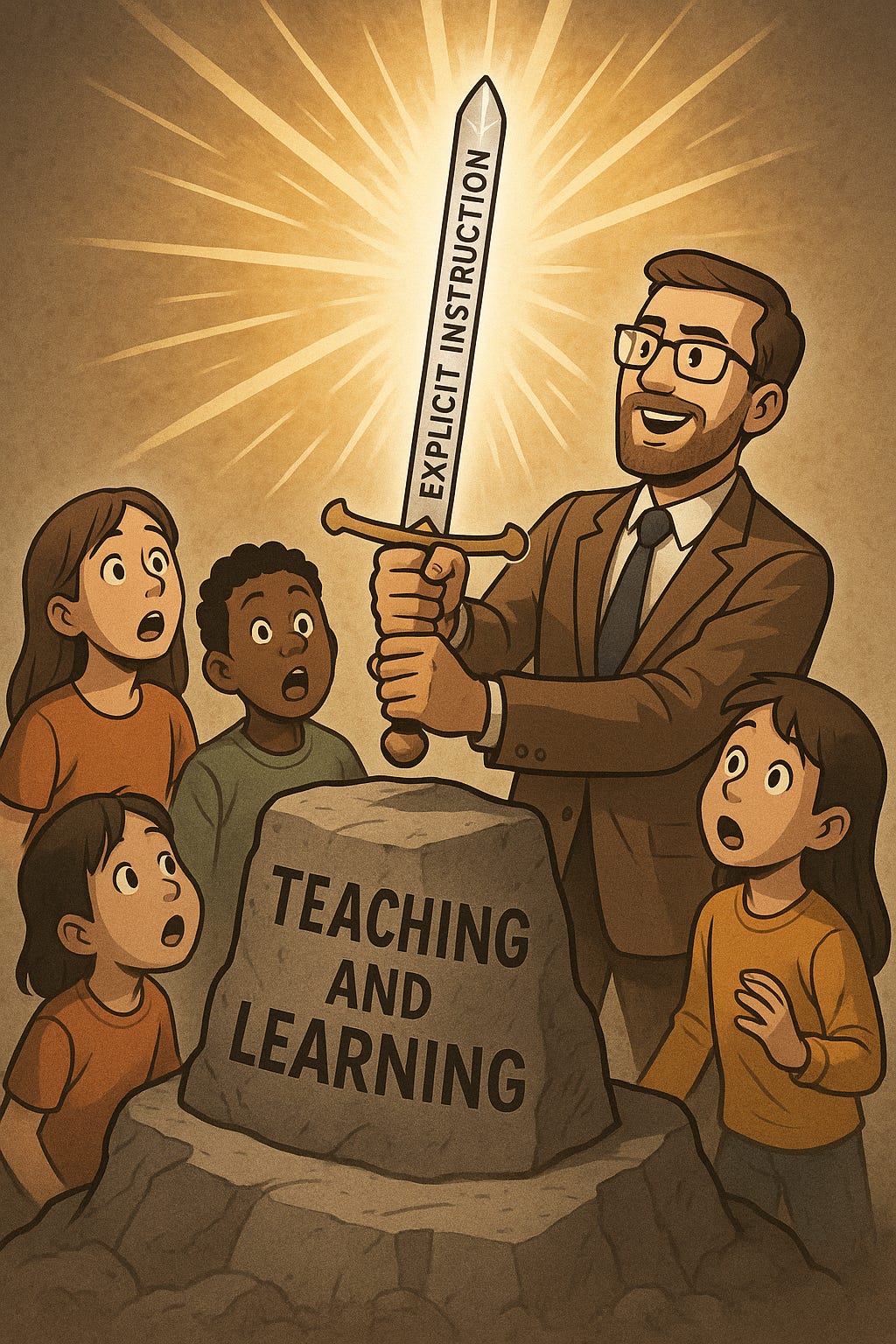

The poverty of Explicit Instruction

In praise of educational complexity and those who revel in it

Explicit instruction, or explicit teaching, is a teacher-led, evidence-based instructional approach that advocates breaking learning down into smaller, manageable parts, providing clear, direct explanations, modeling of skills, and delivering opportunities for practice and feedback. This systematic method aims to optimise learning, reduce cognitive overload, and build students’ understanding and mastery of content by clearly outlining learning intentions and success criteria. It is the paradigm of the moment in many educational jurisdictions (more on this here).

What’s wrong with explicit instruction?

Well, nothing. As I have noted many times in other posts, I’m a fan of being explicit—especially about student thinking! Nor is there anything wrong with (most of) its constituent concepts such as gradual release of responsibility1, and it works fine in a given context. But we must be careful of inferences made from overly restrictive experimental findings.

For the acquisition of basic knowledge, procedures, and psychomotor skills explicit instruction has its place—and, indeed, it is a sad fact that a large part of our curricula is focused on this aspect of education. But there is more to curriculum than developing fixed knowledge structures. And more ways of learning than I-do, we-do, you-do.

Explicit instruction draws heavily, almost exclusively, on cognitive science and the emerging field of neuro-education. Since the brain is the location of all learning, so the narrative goes, it is the source of pedagogical truth. But thinking our current knowledge of the brain allows a full realisation of this truth is not just inaccurate, it is laughable.

When we speak of brains, we speak of that common to all students. When we speak of minds, however, we speak about what is unique to each student. The latter should not be sacrificed on the altar of the former.

The most ancient of pedagogical traps is the belief that one approach serves all contexts. When it comes to explicit instruction, I can hear the traps springing with depressing regularity all around the country.

Such is the nature of explicit instruction as now championed by many, including the Australian Educational Research Organisation (AERO). AERO claims explicit instruction “works in most contexts”, with the clear implication it is universaliable.

The problem is, it does not work in most contexts. Just the acquisition of basic knowledge, procedures, and psychomotor skills as I noted above. That this occupies a large chunk of our curriculum may be the case, but it is not universal.

I leave it for teachers of history, drama, music, philosophy, design, engineering, film and television, legal studies, literature, english, media, psychology, religion or visual arts, to name a few, to say how they feel about reducing their teaching to AERO’s opening gambit:

Explicit instruction breaks down what students need to learn into smaller learning outcomes and models each step. It allows students to process new information more effectively.

Education practice is too often based on research that is either

Restricted to particular contexts,

Designed in ignorance of other potential affects,

Poorly problematised and framed, or

Drawing conclusions using poor inferences.

Generalising findings from basic geometry teaching into, for example, senior history classes, is like using training wheels for motorcycles because they work so well with bicycles; or using the instructions for IKEA furniture to teach custom cabinet making. This type of inference is iconic of explicit instruction.

One of the central tenets of explicit instruction is that it is best used for novices who are beginning the process of knowledge construction. It is also assumed that this describes just about everything a student meets in school. This leads to the conclusion that it should be our dominant (even exclusive) pedagogical approach.

But this is false for several reasons, the most important of which is that thinking involves the manipulation of higher order mental representations that often do not follow algorithmic patterns. The complexity of this higher order thinking is not reducible to I-do, we-do, you-do. And this complexity is present even in the earliest stages of schooling.

The explicit instruction literature is also full of pedagogical gems like this:

If you begin to see kids disengage from the content, their brain has entered information overload.

Yes, that must be it. There could be no other reason. (And I challenge anyone to say what meaning would be lost by replacing “their brain has” with “they have”.)

Moreover, it is a basic tenet of that absolutist neuro-educationalist view that if you get the design right, then all else will follow. It means that learning success is solely a function of the instructional technique. Sure, it needs to be implemented properly but, when so delivered, all will be well. The slide to a compliance culture and the erosion of teacher expertise is a logical consequence.

Two key takeaways

The two critical points I would like to make clear are these:

(1) Explicit instruction is successful within certain limits, just like any pedagogical approach. It cannot do the heavy lifting across all contexts. Forcing teachers to implement explicit instruction in areas where it is not effective or even sensible does nothing to promote teacher expertise or student learning. Indeed, it can have the opposite effect.

(2) You, your students, and your learning environments are all unique. Of course, brain science should not be ignored. But nor should it be elevated beyond its current capacity to offer the most modest of advice. It can not yet fully inform our practice. Pretending otherwise is setting things up for failure.

The American Academy of Colleges and Universities has routinely found that over 90% of employers think that a job candidate’s ability to think critically and solve problems is more important than the area of their undergraduate degree. Thinking is not just an emergent property of content acquisition. We can do better than that.

(Some common responses from explicit instruction proponents have already been dealt with in my previous articles.)

The Role of Cognition in the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model. https://www.edutopia.org/article/role-cognition-gradual-release-responsibility-model/

For those who are interested, I have written a response to this piece here:

https://fillingthepail.substack.com/p/dr-peter-ellerton-faulty-reasoning

"clearly outlining learning intentions and success criteria" That's par for the course in universities nowadays, though more for legal arse-covering than as part of actual practice. If 1 in 100 students has ever looked at the learning objectives I'd be surprised. This seems like something AI would do well.