Beyond Bloom's Taxonomy: the Cognitive Web Model

A better way to identify, develop and assess student thinking

In my last post (below), I showed why using Bloom’s taxonomy was a Bad Idea, and that cognitive skills do not exist in a hierarchical relationship. This is part 2 of 2.

In the spirit of offering solutions—who says contrarians can’t be constructive?—I present here an alternative way of thinking about the cognitive skills/verbs (henceforth sometimes ‘skills’ or just ‘cognitions’), such as justify, evaluate and analyse, that makes focusing on student thinking much easier and actionable.

Naming, identifying and working with cognitive skills is not the only way to meaningfully engage with student thinking. If I left that unsaid, I would be responding to comments for weeks. Of course there alternative approaches: Ron Ritchard and David Perkins’ Thinking Routines, Roger Sutcliffe’s Thinking Moves, Phil Cam’s Thinking Tools—the list goes ever on. A good teacher will find plenty of joy in these.

But an approach explicitly addressing the cognitions is useful. Cognitions are present in syllabus objectives, learning outcomes and assessment criteria. They should be addressed directly. It also represents a more obvious attempt to wrestle cognitive skills away from the hierarchal model. All in all, there are reasons to engage on this ground.

The cognitive web model

Given that the cognitive skills do not exist in any kind of hierarchy, how can we imagine their relationship to each other? Are they, indeed, related at all?

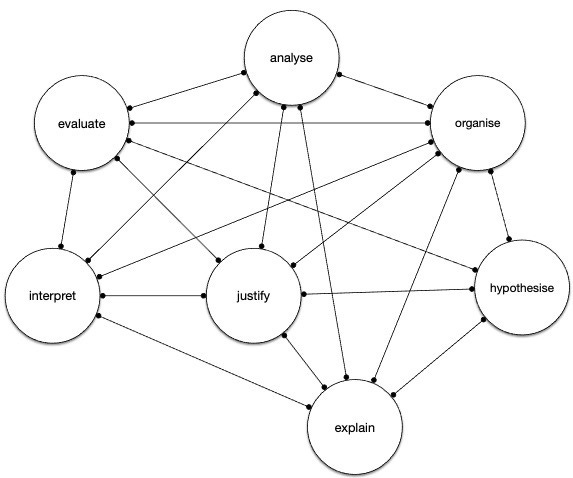

Within our teaching networks, we have developed what I call the Cognitive Web model. This has been rigorously tested as a pedagogical device and has produce significant and positive outputs. In this model, cognitions are represented as ‘nodes’ on a web of inquiry, each connected to others in ways unique to the inquiry underway. The diagram below show how these might be connected in a particular context. To be very clear, I don’t think these cognitions are always connected exactly like this—it depends on the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ of the situation, other mappings are possible.

When you engage in one cognitive activity, plucking the web with an epistemic finger, you will inevitably ‘pull’ others into service. When evaluating, you may need to justify the criteria you use, for example, or analyse an outcome to interpret meaning.

Understanding the cognitions like this allows for a more fluid inquiry, less subject to the artificial and inorganic ‘step by step’ process of marching through fixed cognitive stages. To recall a quote from an earlier post from an 18th century English Headmaster:

…reasoning, never can be reduced to mechanism…

One advantage of Bloom’s taxonomy, it must be said, is that is gave us a relatively small set of skills on which to focus. In the cognitive web, there is no obvious limit to the complexity of inquiry or to the range of skills that might be called on. The cognitive web begins to look like a cognitive quagmire.

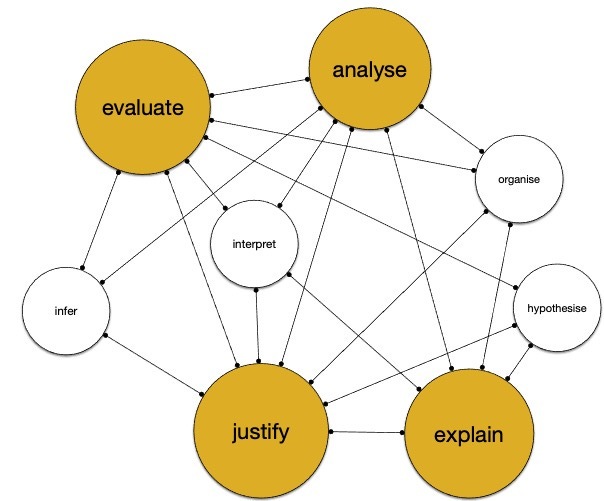

Through research, however, four cognitions have emerged as highly significant nodes on the web, serving as critical points of attention for designing assessment and learning experiences. I call these the Golden Tetrad of skills (GT), as they shine more brightly than most in terms of drawing in other skills and in their importance to developing student thinking. I focused on these cognitions in my last post, and they are worth laying out once more. I’ll then go on to explain why they matter.

The Golden Tetrad of cognitive skills

In a very broad sense, without recourse to definitions that risk being too constrictive:

Analysis involves studying some object or construct and determining its function or purpose; examining the elements that make up that construct and identifying their relationship to each other and their role or function; determining which elements of categories of elements are most relevant or significant; identifying patterns over space or time; other things that might be more discipline area specific.

Justification involves the giving and taking of reasons and explaining why those reasons are the best ones.

Evaluation (noting the root of the word) involves determining what we ‘value’ about something and using this to construct criteria for evaluation.

Explanation involves understanding dynamic, relational aspects between elements and communicating this understanding to others (which separates it from description, which generally requires no understanding—I can describe a soccer match to you but unless I could explain my understanding of the game and how the various elements interact, you would not let me play or referee!).

Of course, what counts as an ‘element’ or a ‘reason’ might change between contexts, but this framing remains coherent across them.

The significance of these skills can be understood as follows:

Analyse is arguable the most common skill, peppering syllabuses, learning outcomes, assessment tasks and criteria sheets. It is also a precursor skill for many others; for example, we can analyse to interpret, analyse to identify, or analysis to categorise, and so on.

Evaluate, and its twin justify, sit at the heart of the identification, analysis, evaluation and construction of arguments, which formalise the giving and taking of reasons (the necessary condition for criticality).

Explain draws on the need to develop and communicate understanding (itself not a cognitive skill but a state to be attained, albeit often in flux—see here).

All of these skills offer means to engage deeply with content and provide a metacognitive and evaluative framework for thinking.

They are also related to one another in powerful and operationally useful ways. For example:

The extent of understanding and quality of explanation can be a function of the depth and breadth of analysis.

The strength of a justification is often a function of the quality of analysis.

The persuasiveness of a justification is often a function of the quality of explanation.

The criteria of evaluation are used to justify and explain decisions (and themselves require justification).

It is important to realise that the Cognitive Web and the GT are simply devices that can be conceptually useful. They can also augment other thinking approaches such as those I mentioned earlier. They are not alternatives, they are cognitive models of what often goes on within them.

When students compare and contrast, for example, they often analyse and identity similarities and differences. When they offer a counter example to a generalisation, they may infer the implications of the generalisation, analyse a context and identify an exception to the rule or category. When they challenge an assumption they may analyse a claim and evaluate and identify the erroneous basis of a chain of reasoning. They may then generate an alternative framing or hypothesis and justify their view.

Questioning, building on the work of others, thinking collaboratively—all these are useful descriptions of levels of action and behaviour that are real and point-at-able. Cognitions simply provide more detail about what might be going on, even if they don’t always tell the full story.

Collaborative thinking

A valuable finding about the GT is that learning activities in which they are targeted are often highly collaborative. We explain and justify towards others; often that which students analyse and evaluate is the thinking of their peers.

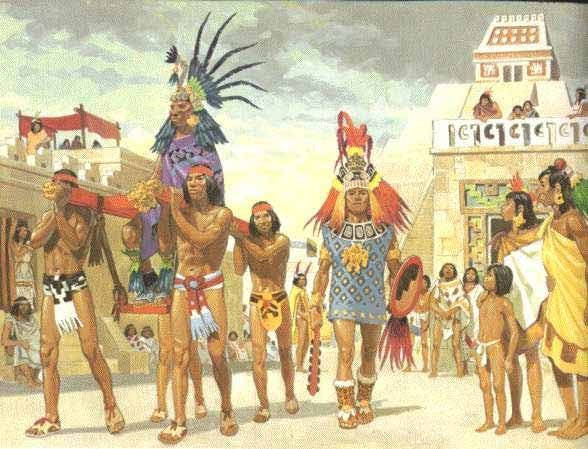

Here’s an example. Present students with the image below and ask “What can you infer about the civilization depicted?” While few things are certain, there are many inferences that could be drawn. Students will need to analyse the image and identify aspects they think are relevant and significant. They will then infer from these observations characteristics of the civilization. They will need to explain why they made these inferences and hence justify their conclusions. Other students can analyse and evaluate these inferences and explain why or why not they find them convincing. The cognitive interplay goes on indefinitely.

Identifying cognitions is part of teacher expertise

All too often we categorise learning activities and assessment based on the content they cover. If we did the activity above, would students go home and say they studied the Aztecs? Because they really didn’t. What they did was develop their ability to analyse images and the thinking of others, explain their reasoning, evaluate the claims and reasoning of their peers and justify their own positions and critiques. Not a bad day’s work. Sure, this could then lead into learning about the Aztecs, in fact it’s a great way to do so, but it need not be the point.

Notice that in this activity I led with the cognitive instruction infer, but I did so in full knowledge of the other skills that would be required, in particular knowing it was a GT activity. This kind of learning design, in which thinking can be targeted with precision and intentionality, is the hallmark of expert teachers in the domain of teaching for thinking.

There are many other things to discuss about the GT, including its role in growing dispositions/virtues characteristic of good thinkers, and the development of norms of collaborative reasoning. But my main point is to provide an alternative to Bloom’s taxonomy. What good teachers do with it is up to them.

Teachers, think about your favorite learning experiences with students. I’ll bet it’s a Golden Tetrad one.

My next post will probably be about the false dichotomy between teaching for thinking and developing content knowledge, but I’m always happy to take suggestions!

Loving your posts Peter! After reading this, I’m really intrigued now on your thoughts about learning intentions and success criteria. How can we best portray the interrelatedness of these cognitive skills to our students but also support them in understanding what success looks like? Maybe a future post? Can’t wait to hear your perspective on the false dichotomy!

Very enlightening article.