Bloom’s taxonomy is wrong—just ask Bloom.

Why we need to move on from this outdated and damaging paradigm.

I noted in my last post that I would look at the consequences of mandating bad practice: this is my first example (and part 1 of 2).

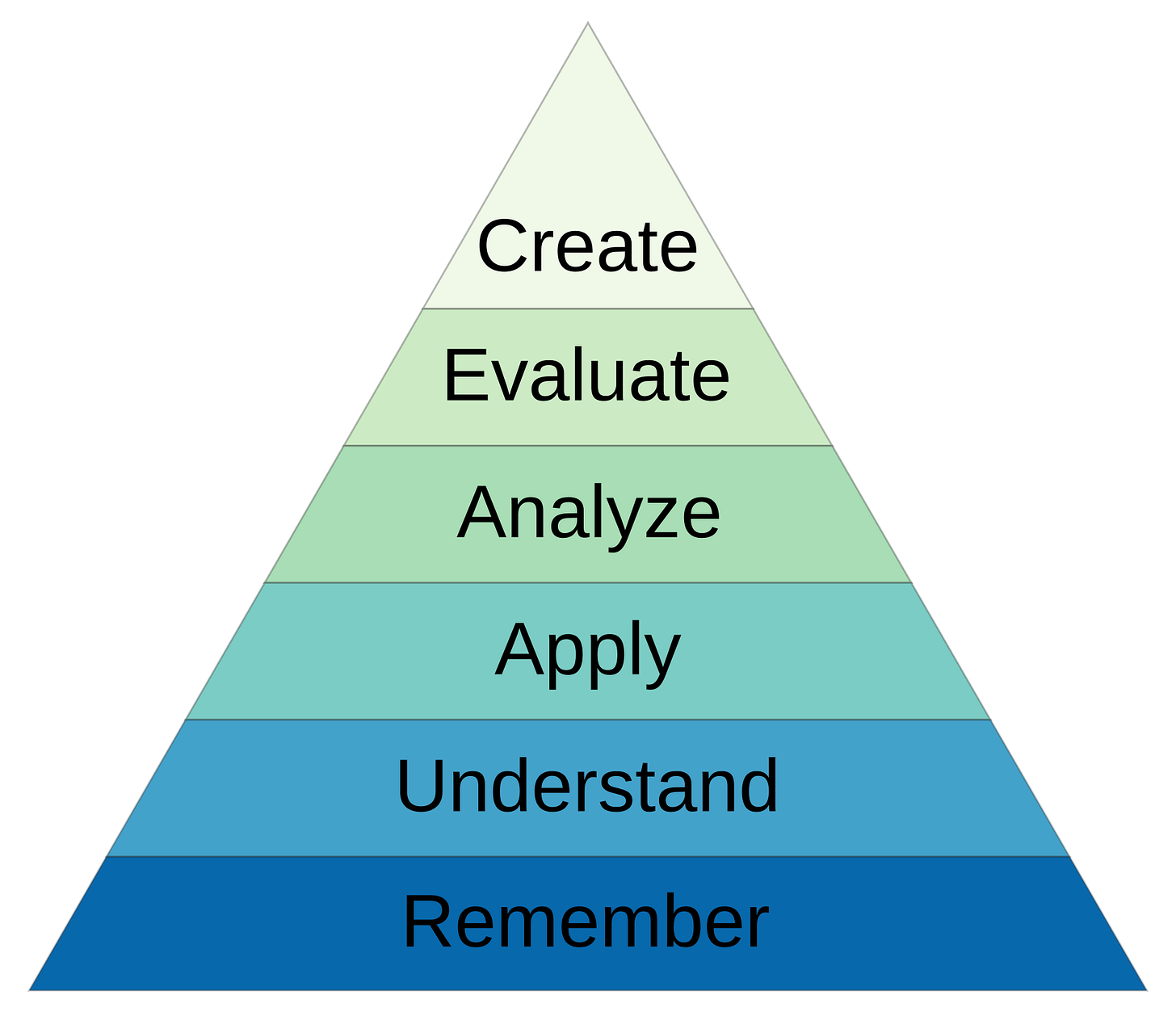

Few educational constructs are as famous or ubiquitous as Bloom’s taxonomy. It permeates every level of education and remains a foundational organising principle in course and assessment design. It tells a story of how cognitive skills (sometimes called cognitive verbs) are related to each other and how we can use this knowledge to improve educational outcomes.

The problem is, Bloom’s taxonomy is wrong. It doesn’t work. No version of it. It does not represent how cognitions are related. There is no hierarchy. The emperor has no clothes. And the emperor has told us so. Stop using it. Stop making other people use it. You are doing damage.

That’s the fun bit! Let’s consider now how this heresy can be justified. Then we’ll look at the kinds of damage Bloom’s can do (and has done).

Before we go there, it would be unjust not to acknowledge that Bloom’s framing of cognitions have helped bring thinking to the foreground of educational discourse. We are in a better place than we might have been otherwise because of it. I may be a bit bullish, but that’s because the inertia is huge. It’s now time to move on and correct some fundamental misunderstandings.

Why Bloom’s taxonomy is wrong

Two fundamental assumptions educators have about Bloom’s taxonomy are that:

Thinking skills can be classified into distinct categories.

Cognitive skills develop in a structured order, from simple to complex.

This is a simplistic way to represent the construct, but it gives us an easy in to discuss what is meaningful about it. Let’s have a look at these, with a verdict on their accuracy at the end of each.

Thinking skills can be classified into distinct categories.

This does not seem problematic at first glance. We can talk meaningfully about cognitions as distinct things. Let me give some examples below about how we could do this without necessarily rigorously defining or contextualising them. We’ll go with the vibe.

Analysis involves studying some object or construct and determining its function or purpose; examining the elements that make up that construct and identifying their relationship to each other and their role or function; determining which elements of categories of elements are most relevant or significant; identifying patterns over space or time; other things that might be more discipline area specific.

Justification involves the giving and taking of reasons and explaining why those reasons are the best ones.

Evaluation (noting the root of the word) involves determining what we ‘value’ about something and using this to construct criteria for evaluation.

Explanation involves understanding dynamic, relational aspects between elements and communicating this understanding to others (which separates it from description, which generally requires no understanding—I can describe a soccer match to you but unless I could explain my understanding of the game and how the various elements interact, you would not let me play or referee!).

Of course, what counts as an ‘element’ or a ‘reason’ might change between contexts—Music to Mathematics, Science to Philosophy—but broadly speaking the distinction holds (I know some people insist that analysis in English, say, is completely different from analysis in Physics, but why, then, are they both called analysis?)

So we can talk about cognitions coherently, each in turn. It is another question, however to ask if they can happen in isolation from each other. But more about that later (next post). Let’s accept Assumption One for the moment.

Verdict: 👍

Cognitive skills develop in a structured order, from simple to complex.

It is a common misconception that the so-called ‘higher order’ skills are composed of the lower order ones, but this is not explicit in Bloom’s work. The relationship is presented not as compositional but as structural. It is better understood as suggesting that to, for example, evaluate in a particular situation, one might need to draw on the lower order skills such as understand and analyze. Evaluation is not composed of understanding and analysis, etc., it is the (potential) cumulative result of them.

But a problem emerges when we ask if it is always the case. Could there be situations in which we need to analyze something before we understand it? It would seem that the answer is only sensible in the affirmative—in fact in most cases, how else could it be?

More than this, is evaluation always more cognitively complex than analysis? Counterexamples abound—you can think of dozens immediately. And when did understanding become ‘lower order’? Isn’t understanding sometimes the highest of our ambitions for our students?

One of the most considered researchers in developing cognitive skills is Robert Marzano, whose work underpins may educational jurisdictions in terms of syllabus and assessment design. This is his view, expressed in The New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, which is less a taxonomy of cognitive verbs as one of information processing during learning (emphasis mine):

The taxonomy [Bloom’s] certainly expanded the conception of learning from a simple, unidimensional, behaviorist model to one that was multidimensional and more constructivist in nature. However, it assumed a rather simple construct of difficulty as the characteristic separating one level from another: Superordinate levels involved more difficult cognitive processes than did subordinate levels. The research conducted on Bloom’s Taxonomy simply did not support this structure. (Marzano, 2006, pp.8–9)

So, higher order skills are not innately more difficult than lower order skills (let’s face it, even identify can be fiendishly difficult). He then notes Bloom’s own doubts:

The problems with Bloom’s Taxonomy were indirectly acknowledged by its authors. This is evidenced in their discussion of analysis: “It is probably more defensible educationally to consider analysis as an aid to fuller comprehension (a lowerclass level) or as a prelude to an evaluation of the material”... The authors also acknowledged problems with the taxonomy’s structure in their discussion of evaluation: “Although evaluation is placed last in the cognitive domain because it is regarded as requiring to some extent all the other categories of behavior, it is not necessarily the last step in thinking or problem solving. It is quite possible that the evaluation process will in some cases be the prelude to the acquisition of new knowledge, a new attempt at comprehension or application, or a new analysis and synthesis”… In summary, the hierarchical structure of Bloom’s Taxonomy simply did not hold together well from logical or empirical perspectives. (Marzano, 2006, pp.8–9)

There you go. There is no hierarchical relationship between the cognitions. That makes evaluating Assumption Two an easy task.

Verdict: 👎

Right, so there are such things as cognitions (cognitive verbs) but they do not sit in relation to each other as Bloom thought.

Two profound problems with continuing to use Bloom’s Taxonomy.

There are at least two major issues that are the result of Bloomian thinking. The first is that, on the assumption that higher order skills such as evaluation are harder than lower order skills like analysis, we should teach first analysis and then evaluation, or first understand before we analyze. What we ignore in this approach is the interplay between the skills, a vital aspect of teaching any of them. It’s a bit like saying we should teach all about predators before we mention prey. This may not be an immediately obvious point, but I will make it the focus of my next post, so more then.

Perhaps more critical is the second problem: using cognitions as discriminators between levels of achievement. For example, the student who evaluates gets an A while the student who simply analyses gets a B or C. A moment’s thought shows why this cannot be the case across all contexts.

Moreover, if the A student evaluates and the B student only analyzes, then what is it they were asked to do? Because it certainly wasn’t analyze or evaluate, because then they would be the criteria and the students would be rated on how well they did them!

And as we saw before, it is absurd to think every case of evaluation is harder than every case of analysis. Of course some could be, but using Bloom’s as an organizing principle means we must universalize it, which reason tells us is not possible.

The moral concern

This is not just an issue of miscomprehension or ineffective practice. Mandating practices we know to be wrong sets up teachers to fail. I have seen teachers very distressed as they attempt to match a task to a criteria sheet using cognitions as discriminators: an excellent piece of work must be downgraded because a student did not ‘accidentally’ evaluate when the task did not explicitly demand it; another is given a good grade because of the presence of basic evaluation and analysis but over a student with excellent analysis.

School leaders have a moral duty not to put teachers in this position. And arguably an even stronger one not to subject students to such incoherence.

At a time when many teachers are deeply unsatisfied with the profession and considering leaving, mandating bad practice is the least valuable thing we can do.

Tear down that poster!

In my next post, I explore an alternative way of thinking about the cognitions. One that is more understandable and actionable.

This reminds me of an old Frank Smith essay, "How Education Backed the Wrong Horse" (1988, p. 109).

https://archive.org/details/joiningliteracyc0000smit/page/109

Also, I want to kick Marzano in the teeth. Maybe he meant well, but at this point I have seen his materials used (and perhaps misused) so much to micromanage teachers for the worse, and to give teachers busy work, that I hardly care.

I feel like having teacher education programs that teach--and evaluate--both systems is the answer. Bloom and Marzano both offer excellent insight into learning. The problem resides in having administrators who have not been taught these systems thoroughly, the good and the bad of them, then evaluating teachers based on a "placemat" of gotcha questions that don't relate to the learning happening in the classroom. I have been evaluated under Bloom's and Marzano by administrators who understood neither. Once I had an administrator who actually understood both. Theirs was the only evaluation I respected and agreed with.